My flower walk guidebook recommended the Gionyama Hiking Trail. This is how I read the opening paragraph before convincing five Explorers ranging in age from five to sixty years to join me in searching for wild camellias last week: Wild Japanese camellia is best seen in its native habitat in Kamakura, on the east side of the Nameri-gawa valley, where a thickly wooded narrow ridge running north-south is kept intact from surrounding urban development. There, the smooth gray-barked trees bloom mysteriously in the shade of tall broadleaved evergreens. Many of its flowers fall along the narrow ridge and are vividly red with a central boss of golden stamens retained in the tubular forms.

This is how I should have read that paragraph: Wild Japanese camellia is best seen in its native habitat in Kamakura, on the east side of the Nameri-gawa valley, where a thickly wooded narrow ridge running north-south is kept intact from surrounding urban development. There, the smooth gray-barked trees bloom mysteriously in the shade of tall broadleaved evergreens. Many of its flowers fall along the narrow ridge and are vividly red with a central boss of golden stamens retained in the tubular forms.

In Japan a "narrow ridge" is an 11-inch wide strip of rocky, muddy, slippery dirt suspended 60-500 feet above the forest it traverses. Live - if you're lucky, that is - and learn.

Following the guidebook's advice, we stopped at Hokaiji temple first to see garden variety camellias.

Following the guidebook's advice, we stopped at Hokaiji temple first to see garden variety camellias. Nicky and Xan are admiring a stray camellia blossom in an old stone lantern on the temple grounds.

Nicky and Xan are admiring a stray camellia blossom in an old stone lantern on the temple grounds. We studied the handy map at the beginning of the trail. What's that Takatoki Harakiri Yagura? Yagura means cave, I learned that a few days ago. Takatoki was the last Hojo regent of the Kamakura shogunate. Harakiri sounds disturbingly familiar. Hmmm. Reiko confirms that we will soon pass the cave where Takatoki ended his own life. Nicky finds this quite disturbing so we don't dally at the cave.

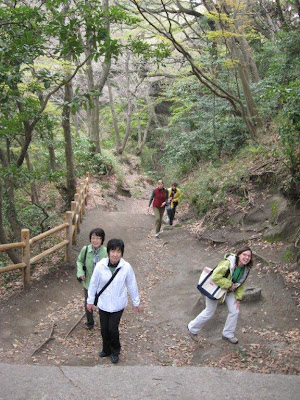

We studied the handy map at the beginning of the trail. What's that Takatoki Harakiri Yagura? Yagura means cave, I learned that a few days ago. Takatoki was the last Hojo regent of the Kamakura shogunate. Harakiri sounds disturbingly familiar. Hmmm. Reiko confirms that we will soon pass the cave where Takatoki ended his own life. Nicky finds this quite disturbing so we don't dally at the cave. The initial incline is deceptively slight.

The initial incline is deceptively slight. This is one of the last pictures I managed to take before my hands were otherwise occupied, gripping tree trunks and branches to avoid an untimely demise. Xan and Nicky kindly offered their hands and helpful tips on where to plant my feet next.

This is one of the last pictures I managed to take before my hands were otherwise occupied, gripping tree trunks and branches to avoid an untimely demise. Xan and Nicky kindly offered their hands and helpful tips on where to plant my feet next. Camellias grow very tall in the wild. Kim, Reiko, and Xan are admiring what I'll bet is a lovely specimen but I can't say for sure since the only camellias I saw were the ones littering the ground at my feet.

Camellias grow very tall in the wild. Kim, Reiko, and Xan are admiring what I'll bet is a lovely specimen but I can't say for sure since the only camellias I saw were the ones littering the ground at my feet. This is an example of the sort of stuff we clambered over but you will just have to use your imagination to sketch in Grand Canyon-type cliffs on either side of the roots.

This is an example of the sort of stuff we clambered over but you will just have to use your imagination to sketch in Grand Canyon-type cliffs on either side of the roots. Near the end of the hike there's a nice flat resting place offering a magnificent view. The only thing that could get me back on that ridge was the promise of waffles.

Near the end of the hike there's a nice flat resting place offering a magnificent view. The only thing that could get me back on that ridge was the promise of waffles.